If you are building an app, a backend service, or an internal tool, adding text messaging can feel deceptively simple. You make an HTTP request, a phone pings, you ship it.

Then the messy bits begin.

Messages split into multiple parts because of emojis. A sender name works in one country and fails in another. Your webhook times out, so delivery receipts arrive late, then repeat, then arrive again. A user tries to opt out, but your system keeps sending anyway, and now you have a compliance problem.

We will go over:

Why SMS is never “just one request” once you ship to real users

The hidden ways costs jump, especially with Unicode and emojis

What breaks most often in production and how to design around it

How to handle delivery updates safely when providers retry and events repeat

The minimum architecture that keeps messaging stable as volumes grow

The compliance basics that must live in your data

What an SMS API Does Inside a CPaaS Setup

An SMS API is an HTTP interface that lets your backend send A2P messaging traffic. A2P means application to person. Your app triggers the message, not a human typing in a chat screen.

In practice, an A2P messaging platform sits between your systems and mobile networks. You send a request such as “deliver this content to this number,” and the platform handles routing, carrier rules, delivery receipts, retries, and reporting.

A CPaaS is the broader category that wraps messaging into developer-friendly building blocks. Many CPaaS platforms offer more than SMS, including richer channels and verification flows, but SMS is still a common first integration because it is broadly supported on phones worldwide and fits many transactional use cases.

Even as richer channels grow, A2P messaging at scale is still enormous.

Going by ITU numbers, there are 112 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants. A MobileSquared market report estimates A2P SMS traffic to range at 2.11 trillion by 2029. This shows that SMS remains a default path for OTPs, alerts, and operational messaging.

You are building on top of a channel that is globally relevant, but also shaped by real-world constraints like fraud controls, country rules, and carrier filtering. Your integration needs to respect that from day one.

Pick One Use Case First and Be Specific

A clean first integration starts with a single use case, not “send all the messages.” The use case drives everything else, including how you handle consent, how you store logs, and what you put in the webhook payload.

Start with one of these:

Account verification and OTP

This is classic A2P. Your message must arrive quickly and predictably. You need strong anti-abuse controls because OTP endpoints get attacked by bots.

One reason this matters is artificially inflated traffic, where automated systems generate OTP requests at scale. Juniper Research has highlighted this as a real fraud vector in A2P SMS.

Transactional notifications

Order confirmations, shipping updates, appointment reminders, incident alerts. Here you care about delivery receipts, message content quality, and quiet hours.

Two-way support and service workflows

You send a prompt, users reply, your system routes responses. This brings extra complexity around inbound numbers, conversation state, and opt-out behaviour.

Marketing and lifecycle messaging

This is the highest risk category for compliance and filtering. It can work well, but only when you treat opt-in, frequency, and relevance as engineering requirements, not just marketing preferences.

Build the Integration in a Sequence That Avoids Rework

A common mistake is to start by wiring a “send SMS” button, then bolt on compliance, then bolt on webhooks, then bolt on security. You end up rewriting core parts of the flow.

This sequence tends to hold up better.

Step 1: Decide how your sender identity will work

Your sender identity is what the user sees as the “from” of your message. Depending on the country and the route, you may use:

An alphanumeric sender ID such as your product name

A long number that can receive replies

A short code in markets where that is required and approved

From an engineering angle, treat sender identity as configuration, not hardcoded text. You will want per-country rules later, and you may want different identities for OTP versus support.

Also decide if you need replies. If your first use case is OTP, you often do not need inbound messaging. If your first use case is support, you probably do.

Step 2: Treat consent and opt-out as part of the API design

Even if you are starting with transactional messages, you should implement opt-out behaviour early. Carriers and industry frameworks often expect standard opt-out keywords.

CTIA’s Messaging Principles and Best Practices describes opt-out keywords such as STOP, and highlights that recipients should be informed about how to opt out.

This is not only a policy detail. It affects your database design. You need a place to store:

- phone number

- opt-in status and timestamp

- opt-out status and timestamp

- source of consent

If your platform supports opt-out features, you still want your own system-level record so you do not keep triggering sends to users who have already said no.

For US-specific risk, the TCPA is the law that often shows up in lawsuits and enforcement conversations around automated calls and texts, and penalties are commonly range at $500 to $1,500 per violation depending on circumstances and intent.

If you are shipping a product that sends messages to US numbers, it is worth having a short internal checklist reviewed with legal counsel early.

Step 3: Create API credentials and lock them down properly

Most production messaging incidents start as secret-handling incidents.

In SMS.to, you generate credentials inside the API Clients section, and you can choose between API key authentication and client/secret flows. There’s also optional IP whitelisting per API key, which is a practical control for backend services running from known infrastructure.

With this system, keys can be generated in a “secure” long format, and a shorter format exists for older third-party tools that cannot handle long keys. For modern server-side apps, long keys are the safer default.

A production-ready baseline looks like this:

- Store your API key in a secrets manager, not in source control

- Inject it at runtime through environment variables

- Rotate keys on a schedule and after any suspected leak

- Prefer server-side sends only, never from a mobile app or browser

- If IP whitelisting fits your deployment model, use it

Step 4: Send your first message using the smallest possible code path

For a first integration, you want one path that works end-to-end:

Your app triggers a send

The platform accepts it

The message is delivered or fails

You receive a callback

You store the outcome in your system

See an /sms/send endpoint and showing a basic structure using an HTTP POST with a Bearer token: SMS.To

Here is a minimal cURL example written in the same shape, with placeholders you can swap.

curl –location ‘https://api.sms.to/sms/send’ \

–header ‘Authorization: Bearer YOUR_API_KEY’ \

–header ‘Content-Type: application/json’ \

–data ‘{

“to”: “+15551234567”,

“message”: “Your verification code is 482913. It expires in 5 minutes.”,

“sender_id”: “YourBrand”,

“callback_url”: “https://api.yourapp.com/webhooks/sms-status”

}’

A few practical notes before you ship this:

- Format numbers in E.164 where possible, with a leading + and country code.

- Keep OTP content short and predictable. Long OTP messages can split into multiple parts and delay arrival.

- Use a dedicated callback endpoint for status updates, and make it return HTTP 200 quickly.

Step 5: Handle delivery status callbacks without losing your mind

A “send” response only tells you the platform accepted your request. Delivery status comes later, and it is an event stream.

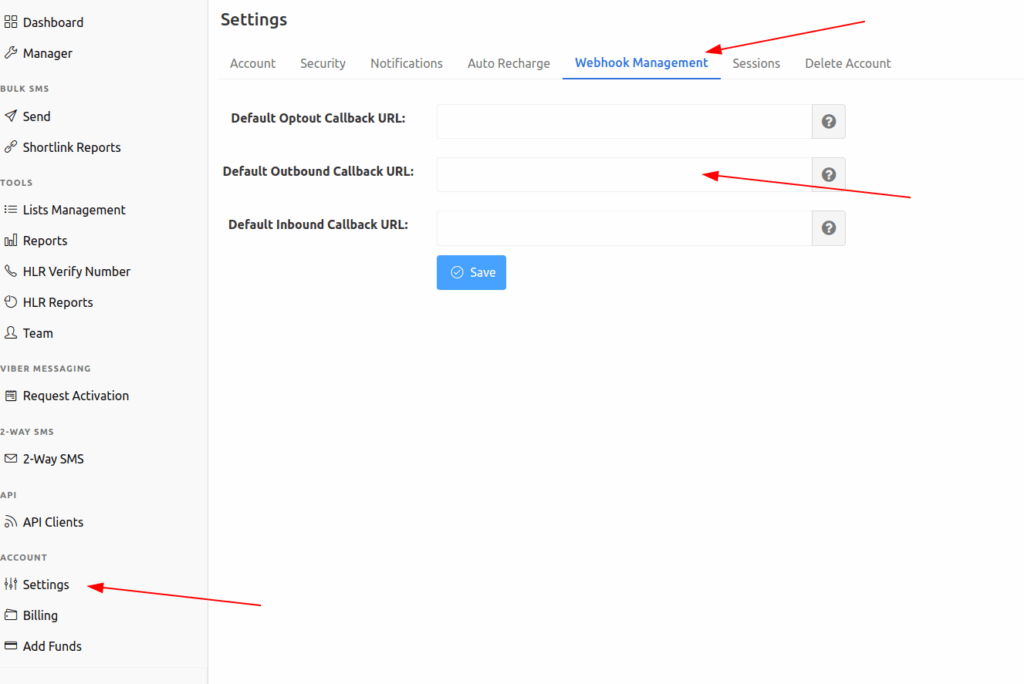

SMS.to provides outbound message status callbacks that you configure in your account settings, and it posts status updates to your endpoint using form-encoded POST data. The payload includes fields such as trackingId, messageId, phone, status, parts, and price.

Also note:

- Your webhook endpoint should respond in under 3 seconds, otherwise the connection can be dropped and the callback retried later.

- If your endpoint fails or does not return HTTP 200, callbacks can be retried on a schedule that steps out over time, starting with a retry after 1 hour and extending to longer intervals.

That means you should build your callback handler like this:

- Validate the payload

- Put it on a queue for processing

- Return HTTP 200 immediately

- Process asynchronously

- Make processing idempotent

Idempotent means “safe to repeat.” Your handler should accept duplicates without corrupting state. A simple way is to store statuses keyed by messageId and only update if the new status is later in your lifecycle ordering.

Step 6: Verify callbacks so you do not accept forged delivery events

If your callback endpoint is public on the internet, anyone can POST to it. If you use callback events to trigger user-visible actions, forged events can become a security incident.

SMS.to offers signed webhooks through an X-SMSto-Signature header so you can verify that an event came from SMS.to and was not modified in transit. Each endpoint has its own webhook secret.

For a first integration, do at least these:

- Verify the signature for every inbound webhook event

- Reject events that fail verification

- Log failed verification attempts with IP and headers

- Keep webhook secrets in your secrets manager

Step 7: Stop unexpected message splitting before it hits your billing and your UX

SMS looks like a 160-character box until you ship an emoji and your 70-character limit arrives.

At the protocol level, concatenated SMS uses a header that reduces the usable characters per segment. 3GPP documentation describes these effective limits:

160 GSM 7-bit characters in a single message

70 UCS-2 characters in a single message

When concatenated, 153 GSM 7-bit characters per segment

When concatenated, 67 UCS-2 characters per segment

For your first integration, build a small “message budget” function that:

Detects when your content contains non-GSM characters

Estimates how many segments it will use

Prevents accidental long content for OTPs

Logs when a message crosses into multiple parts

Example:

“Your code is 482913” is short and safe

“Your code is 482913 ✅” might switch encoding and reduce your single-message limit depending on the character set, which can split messages and raise cost

If you are sending to markets that use non-Latin scripts, assume UCS-2 will be common and design around the lower per-part limits.

Step 8: Add a queue before you scale traffic

For your first integration, you might send one message per event. As soon as you add password resets, logins, and signups, you have bursts.

A queue keeps your API calls controlled and lets you manage retries without hammering your messaging provider or your own database.

A simple model looks like this:

- Your app writes a “message job” into a table or queue

- A worker pulls jobs in batches

- The worker calls the SMS API

- The worker stores the platform’s tracking identifiers

- Webhooks update final delivery state

Use exponential backoff for retries when the API call fails due to network errors. Do not retry endlessly. Store a retry_count and a next_attempt_at timestamp.

Step 9: Build observability you can use during an incident

When messages fail, you will get questions you need to answer quickly:

- Which users are affected

- Is it one country or all countries

- Is it one carrier route or all routes

- Is it only OTP or also notifications

- Did we send, and did it deliver

SMS.to’s callback payload includes parts and price, which are useful for quickly spotting segmentation issues and unexpected billing impact during a release.

At minimum, log:

- your internal message ID

- platform message ID and tracking ID

- destination number and country

- message type such as OTP or notification

- timestamp for send request

- timestamp for each status callback

- final delivery status

Also set basic alarms:

- spike in send errors

- spike in webhook failures

- webhook processing latency

- unusual increase in parts per message

A First Integration Example You Can Model

Here is a scenario that stays small but production-friendly:

Use case

Your app sends an OTP during signup.

Components

- API server

- Message queue

- Worker

- Webhook receiver

- Database tables for users, message jobs, message statuses

Flow

User enters phone number

You create an OTP and store a hashed version

You enqueue an SMS job with type otp_signup

A worker sends the SMS via /sms/send

You store the platform identifiers in your messages table

Webhook events update status as they arrive

If delivery fails, you decide whether to allow resend or switch channel

SMS.to’s product set includes a dedicated Verify API that can route OTPs across multiple channels with fallback, which becomes relevant once you outgrow a single-channel OTP approach. For a first integration, you can keep it SMS-only and still design your schema so you can add more channels later.

The Top Production Failures You Can Prevent in Week One

Keep an eye out for these:

Wrong number formats

Most messaging bugs start here. Standardise number storage. Do not accept “0700…” into your send pipeline. Convert to E.164 at the edge and reject what you cannot parse.

Callback endpoint timeouts

With SMS.to there is a 3-second window before it drops the connection and retries later. If you do heavy work inside your webhook handler, you will create delayed and duplicated events. Put work on a queue and return 200 fast.

Duplicate callbacks treated as new events

Retries happen. Your handler must be idempotent. If you treat every callback as a unique event that triggers user-facing actions, you will cause repeated notifications and support tickets.

Content that suddenly becomes multipart

A small content change can raise segments and cost. Track parts from callbacks and alert on shifts.

Opt-out not respected

Your system should block sends when a user is opted out, even if your product team is “only testing.” This is one of the easiest mistakes to prevent with one database flag.

Where A2P Messaging is Heading and How That Affects Your Integration Choices

Business messaging traffic is growing across multiple channels, including SMS, RCS, and OTT messaging apps. Juniper Research has projected growth in total business messaging traffic from 2 trillion messages in 2025 to nearly 3 trillion by 2030 when you count these channels together.

For your first integration, the practical implication is not “ship every channel now.” It is:

- Design your message model to support multiple channels later

- Separate message intent from channel selection

- Keep consent records at the user level, not the channel level

- Log outcomes in a way that stays comparable across channels

That is how you move from a single SMS API call to a durable CPaaS-grade messaging layer.

Go-live Checklist for Your First SMS API Integration

And now for a final check to ensure your system is operating optimally:

Security and access

- API key stored in a secrets manager

- No API calls from client-side code

- Optional IP whitelisting where it fits your deployment

Reliability

- Send flow uses a queue and worker

- Webhook handler responds quickly and processes asynchronously

- Idempotent processing for repeated callbacks

Integrity

- Webhooks verified using signature support

- Delivery states stored with a clear lifecycle

Content and cost control

- Message length budgeting with GSM and UCS-2 segmentation rules

- OTP content kept short and consistent

- parts tracked in logs to spot silent cost increases

Compliance basics

- Stored opt-in and opt-out records

- STOP and other opt-out patterns handled in your logic

From One Request to Production-Ready Messaging

Your first SMS API integration should not be a single HTTP request living in a controller. It should be a small messaging system with four solid foundations:

- controlled sending through a queue

- verified webhooks for delivery updates

- message design that avoids accidental multipart content

- consent and opt-out tracking baked into the model

That gives you a clean base for A2P services as you grow, and it puts you in a good place to add additional channels later without ripping up your core logic.